The Call Before Dawn

On Saturday morning, when most folk were still tangled up in warm duvets, I found myself crawling out of bed earlier than usual. My wee wife lay there half-asleep, warm as a turf fire, the sort of sight that makes you question every choice that has led you there. But the job would not wait.

Out I went into the grey hush, dragging on heavy gear: thick waterproofs, gloves, mask, goggles, the full battle kit. The sort of set-up that turns every move into a fight with yourself. Sure enough, after ten minutes or so, my hands were burning, legs scratched and bleeding, arms bruised, sweat running down my back. The goggles steamed up so badly I might as well have been working blindfolded, and just another 4 hours of this to go!!

Somewhere in between the stings and the slow drip of sweat, a question kept rattling around my head: What’s this work really worth?

By the Litre

Standing there on Saturday, soaked to the skin and stung to bits, I thought maybe I have been charging customers all wrong. Maybe it is time to start charging by the litre of sweat.

A new kind of invoice:

Five litres of sweat @ £150/litre = £750

Thirty nettle stings @ £10 each = £300

Twenty tightly lodged thorns expertly extracted @ £15 each = £300

Gloves, now resembling damp cardboard = £25

Goggles, traumatised beyond repair = £40

Satisfaction of finishing what others will not even start: beyond price.

Sounds half-mad, but behind the joke sits a hard truth. Real graft is fast becoming a rare commodity, with so few now willing or even able to take it on, and as such the price folk are willing to pay for it is going up.

The Week Before

That question had already started haunting me the week before. I was on a painting job at a house where the owner was getting an old fence and shed ripped out to make space for a new fence. You would think it would be straightforward enough, a job most able-bodied lads here could have tackled in their sleep not so long ago.

But there they were, two fully qualified, time-served carpenters, men earning more than many doctors, standing knee-deep in muck, sweat pouring off them, hacking away at an old root system that refused to budge.

Why? Because the owner could not find anyone else willing, or able, to do it.

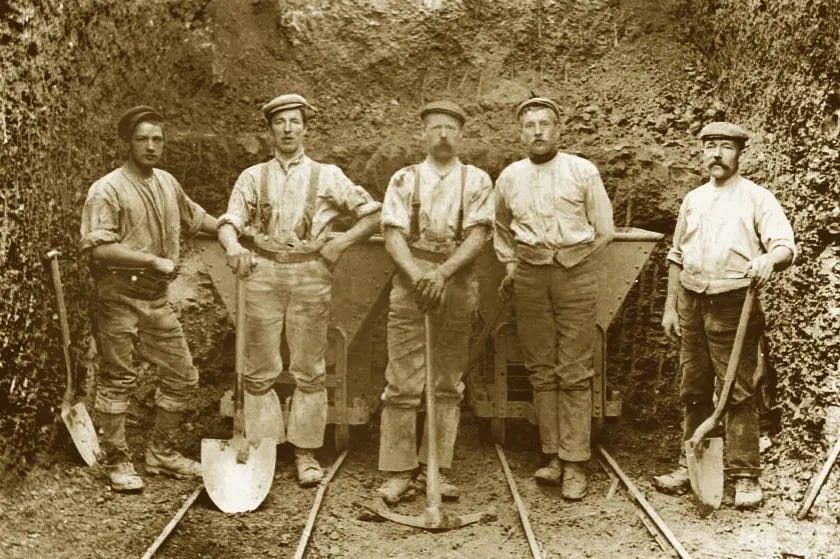

It was not that long ago we had lads to spare for that kind of graft. We exported them in droves, Irish navvies digging canals and railways in Britain, Ulster-Scots hacking out the Appalachian frontier, Scots cutting paths across Canada. Men who would swing a pick before breakfast and be ready for more by supper.

Now the old grafters are getting thin on the ground. And the young ones? Many would not know which end of a shovel to hold, never mind how to use it.

When Graft Became Gold

History is full of warnings about what happens when real graft runs scarce.

Take the Black Death back in the 1300s. Near half of Europe was wiped out, and all of a sudden there were not enough strong backs left to work the fields, fix the roads, or keep the towns running. Overnight, the ordinary labourer, the man no one looked at twice before, became worth his weight in silver. Wages shot up, and for once the fellow with a spade in his hand had the upper hand. Kings and lords tried to lock wages back down with laws like England’s Statute of Labourers, but it was like trying to nail fog to a wall.

Same thing after the big wars. After the First World War, with so many young men gone, there were not enough hands left to keep the wheels turning. Workers could finally ask for better pay and better conditions, and they often got them. After the Second World War, it was the same story again. Rubble everywhere, not enough able bodies to clear it, so graft suddenly held real power.

When bodies are thin on the ground, graft turns to gold.

We might not have a plague or a war right now, but we have got something else, a generation that is just not strong enough or not willing enough to do the hard stuff. Soft living, screens, and a culture that runs from discomfort have left us with fewer and fewer who can stand all day in the muck, swing a pick, or haul a load without falling to bits.

Real graft is fast becoming a rare commodity, with so few now willing or even able to take it on.

The Vanishing Strength

It is not just that young fellas today do not want to graft, plenty simply cannot. Their bodies are not built for it anymore. Years hunched over screens, no rough backyard games, no odd jobs that toughen you up.

A strong back used to be a man’s proudest asset, his quiet badge of honour. Now, worth is measured in clean hands and clever captions.

The Big Switcheroo

For years, every young lad was told to steer clear of trades. "Get into tech. Get a nice office job. Keep your hands clean, stay smart, stay comfy."

The ironic twist though, is that a lot of those very jobs, are the first ones on the chopping block now. AI is coming for them fast, the office lads, the brand consultants, the junior coders, the spreadsheet warriors.

Those "safe" careers, once the golden ticket, are looking shakier by the day. Meanwhile, no chatbot is getting up at 4 a.m. to stand in a bog. No AI is digging out an old root or lugging rubble through the rain. There is no digital shortcut for sweat.

A Necessary Caveat

I wrote an essay not long ago called "The Age of the Educated Man is Over, the Time of the Labouring Man Has Begun."

The Age of the Educated Man is Over, the Time of the Labouring Man Has Begun

For years, society has been pedalling a dream: get a degree, and success will follow. You’ll be whisked into an office with air-conditioning, sit in endless meetings about "strategic alignment," and enjoy a steady salary as you gaze at pie charts on a screen. That was the dream, a neat little plan handed down to young men as the only way to a prosperous…

It still is one of my most popular articles, it struck a chord with many, but I was rightly pulled up by someone for romanticising manual work.

They were dead right. It is dangerous. It is hard. It often (certainly in the past) does not pay well, and it can chew up your body long before your mind is ready to stop. I know it myself. After hurting my Achilles, I was out for a good while. No graft, no income, when your body is your living, an injury can leave you lower than you would ever expect. However, a bit like soldiering, it calls to something deep inside a man, it is the very difficulty of the task that makes it attractive.. I know when I joined the military, one of the reasons I did so, was because it was always seen as one of the hardest things to do.

The Deeper Cost

We have built a world that barely knows how to value real, physical work anymore. A man is "successful" if he spends all day shuffling slides, comes home with smooth hands, and counts his worth in likes and shares.

But when the pipes burst, the roof caves in, or the roads wash away, there is no app coming to save you. You cannot download grit or outsource courage. When real trouble shows up, we will find out fast who can stand in the muck and finish a job that hurts.

A man who lives by his sweat knows truths that no seminar or self-help book can teach. Every cut, every bruise, every heavy breath is a lesson. The world will not bend just because you want it to, strength is earned the hard way, and sometimes the meanest jobs often show a man’s real worth.

So What is Our Sweat Really Worth?

So, what price the sweat of your brow?

Next time you see a man soaked through, standing in muck with a spade in his hand, stop and ask yourself: What is that work really worth? How many would trade places with him, even for a day? How many even could? What would I be willing to pay, not to have to do that?

Maybe it is time we really did start charging by the litre of sweat. Maybe then we would remember what actually keeps the world turning, and what makes many a man truly valuable. When the bright screens go dark and the consultants are left blinking in the cold, there will still be a few standing, bruised, soaked, stung, but upright, and more valuable than ever.

"In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return." Gen 3:19

If you enjoy my work and benefit from it, then please consider a paid subscription. I believe in the importance of this work, I want to keep it free to read for everyone and away from paywalls, this means I rely on your generosity, and for just the price of a beer each month, you can help contribute to this endeavour.

I’ve done both kinds of work—laid asphalt, built houses, bucked hay, etc.—and I’ve been an editor and a college professor. Hand or head—you get something from each, you lose something in each. The world needs both. But damn, I gotta agree with you about the young men in my neighborhood. Big screens make for soft, Pillsbury Doughboy bellies, and I can’t get a one to do any hard chore—for good cold hard cash.

Great read and oh so true. I’m one of those educated types, earning my living from my intellect, safe in the knowledge that I’ve only a few years left before I turn off the computer for good.

Yet, even in this environment, finding a graduate who is willing to do any more than the bare minimum is becoming increasingly difficult. There are exceptions (and they stand out like a rose in a thorn field), but for the main part they are entitled, lazy and completely lacking in resourcefulness.

Graft, regardless of the setting, is a rare commodity